Imagine strolling through the bustling streets of New York City’s Meatpacking District, where a once-derelict elevated railway line, abandoned for decades, now thrives as the High Line – a lush, linear park teeming with locals and tourists alike. This transformation didn’t come from bulldozing the past; it emerged from cleverly repurposing an industrial relic into a green oasis that boosts community spirit and local economies. From an initial city investment of $115 million, the High Line has stimulated over $5 billion in urban development and created 12,000 new jobs. Stories like this highlight a growing shift in urban development: adaptive reuse, where existing buildings are retrofitted for new purposes, often outshining the traditional demolish-and-rebuild approach. In an era of climate urgency and housing shortages, this strategy offers a smarter path forward. This blog explores why adaptive reuse is gaining traction globally, drawing on environmental, economic, and social benefits, while addressing its challenges.

The carbon conundrum: Embodied vs. operational emissions

For years, the focus in building has been on operational carbon – the emissions from heating, cooling, and powering structures. But as renewable energy grids expand, embodied carbon – the emissions locked in during material extraction, manufacturing, and construction – is emerging as the bigger culprit. In high-performance buildings, embodied carbon can account for up to 50 per cent of total emissions over a 50-year lifecycle, with projections showing it could dominate as operational emissions drop.

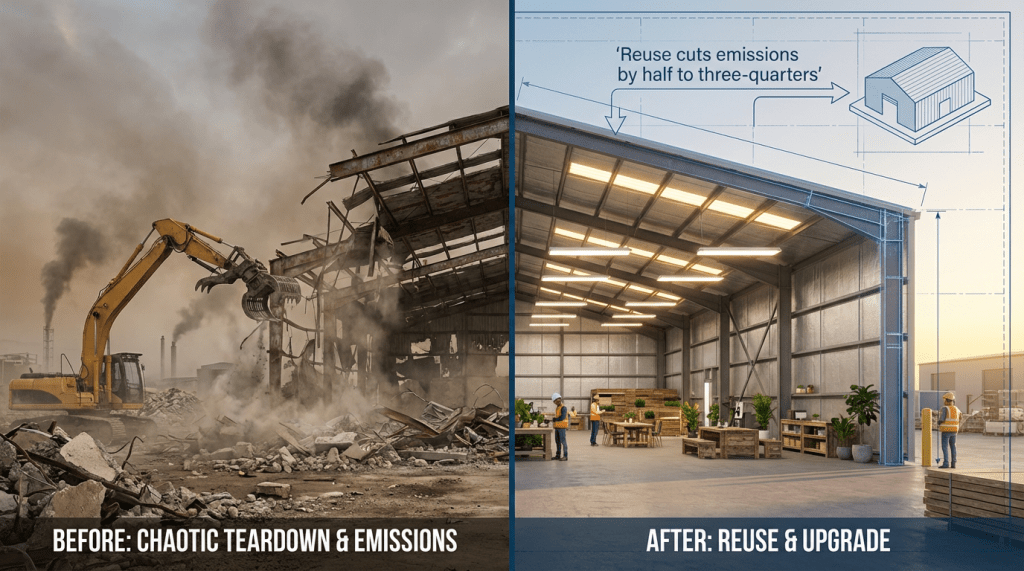

Picture a developer in Toronto facing a choice: tear down an ageing factory or retrofit it into lofts. Demolishing releases a massive upfront carbon spike from waste and new materials, while reuse preserves the structure’s embodied energy. Studies show adaptive reuse can slash upfront emissions by 50-75 per cent compared to new builds, avoiding the energy-intensive production of concrete and steel. In Europe, where grids are decarbonising faster, this split underscores the need to prioritise reuse. This “time value of carbon” means new constructions might take decades to offset their initial debt, missing critical 2030 climate targets. Circular economy principles amplify this: by keeping materials in use, reuse aligns with reducing global CO2 from building materials significantly.

Economics of regeneration: Cost, risk, and value

Beyond the environment, adaptive reuse often stacks up economically against new construction. Repurposing can cut costs by 16-30 per cent, mainly by skipping foundation work and leveraging existing infrastructure. Take a developer in London converting a Victorian warehouse: timelines shrink by up to 18 per cent, reducing holding costs and speeding market entry.

But risks loom. Hidden issues like corrosion or outdated systems can inflate budgets, requiring higher contingencies. Advanced tech, such as 3D scanning, helps mitigate this. Positively, reuse offers a “revitalisation advantage” – combining direct savings with environmental perks. A Warsaw industrial project at Radex Park Marywilska achieved 56.95 per cent direct cost savings and a Savings Ratio of 1.93 (meaning PLN 1.93 returned for every PLN 1 invested), while preventing 48,217 tonnes of CO2 emissions and diverting 72,315 tonnes of waste, as it is discussed in episode 393 on the What is The Future for Cities? podcast.

Market differentiation adds appeal. In competitive real estate, heritage elements like exposed brick command premium rents, as seen in Brooklyn’s warehouse conversions drawing creative tenants. Globally, this “heritage premium” fosters economic regeneration, with adaptive projects spurring jobs and tourism while preserving cultural fabric.

Social dynamics, psychology, and urban identity

Cities aren’t just concrete; they’re tapestries of human stories. Adaptive reuse nurtures “place attachment,” the emotional bonds fostering community belonging. In Berlin, repurposing Cold War-era bunkers into cultural hubs has healed historical divides, reducing alienation and boosting mental health through restorative environments.

Consider a family in Cape Town relocating to a retrofitted colonial mill: the preserved façade evokes continuity, enhancing life satisfaction and social cohesion. Heritage preservation links to well-being, with studies showing historic settings lower negative emotions and strengthen identity. Economically, it revitalises neighbourhoods, as in Detroit‘s tax credit-driven regenerations creating jobs and pride.

Engineering the transition: Structural upcycling and innovation

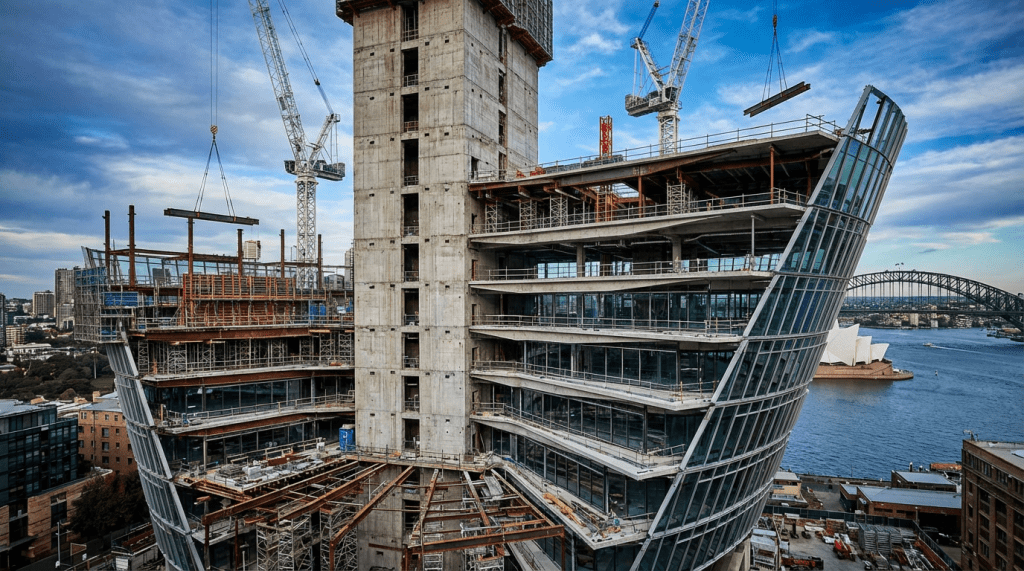

Innovation bridges old and new. Sydney’s Quay Quarter Tower exemplifies “upcycling”: retaining 65 per cent of the original structure (columns, beams, slabs) and 95 per cent of the core, saving approximately 12,000 tonnes of embodied carbon – equivalent to tens of thousands of flights between Sydney and Melbourne – while delivering estimated savings of AUD $150 million and 12 months in construction time. Avoid “facadism” – keeping just the skin while gutting interiors – which wastes embodied carbon. True integration demands carbon-fibre wrapping or bracing in seismic areas. Future-proofing via “design for disassembly” shines in Rio’s Olympic arena, dismantled into schools, slashing embodied carbon significantly. These feats show engineering can scale reuse from boutique to skyscraper levels, aligning with circularity to treat buildings as “material banks”.

When new construction prevails: A balanced perspective

While adaptive reuse often shines as a clever way to breathe new life into old structures, it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution. In some cases, demolition followed by fresh construction emerges as the more practical choice, ensuring resources are used efficiently without forcing a square peg into a round hole. Picture a developer eyeing a crumbling warehouse in a rapidly growing suburb of Chicago: the building’s foundations are shot, riddled with cracks from decades of neglect, and retrofitting would demand millions in structural reinforcements just to meet basic safety codes. Here, starting from scratch allows for a design that incorporates modern earthquake-resistant features and expansive layouts tailored to current needs, ultimately proving more cost-effective in the long run.

Research highlights specific scenarios where new builds take the lead. For instance, when an existing structure is obsolete or requires extensive alterations that outweigh the benefits of retention, demolition can be the smarter economic move. Safety and functionality play key roles too. Hazardous buildings with issues like asbestos, severe corrosion, or non-compliance with seismic standards often make reuse unviable, risking lives and inflating budgets.

Each project demands thorough investigation. Lifecycle assessments, cost-benefit analyses, and site-specific evaluations – including environmental impact, market demand, and regulatory hurdles – are essential to determine the optimal path. Blindly favouring reuse can lead to inefficient resource allocation, just as hasty demolitions might squander valuable assets. By weighing these factors carefully, urban planners and developers can make informed decisions that truly serve communities, blending the old with the new in ways that make sense for the future. This is also the experience of Harriet Shing, Minister for Housing and Building, Precincts and Development Victoria, and Suburban Rail Loop, who discussed the need to investigate this need case-by-case in episode 394 on the What is The Future for Cities? podcast:

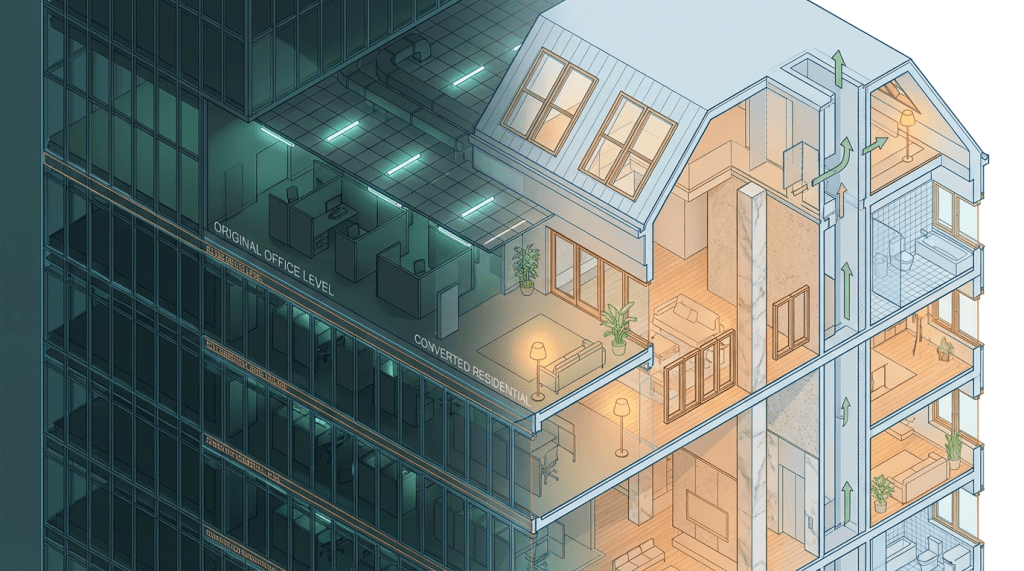

The office-to-residential conversion conundrum

Post-COVID, vacant offices contrast housing crises. In New York City, conversions have surged, with 4.1 million square feet commenced in 2025 alone (surpassing all of 2024), driven by high vacancy (around 22 per cent) and supportive policies like tax incentives. Yet challenges abound: deep floor plates block natural light, requiring costly atriums; centralised plumbing doesn’t suit unit bathrooms; and structural upgrades can be expensive.

Successes favour older buildings with narrower plates. Hybrid models or incentives could unlock potential, but without addressing barriers, conversions remain selective.

The adaptive reuse vs. new build debate boils down to real impacts: reuse minimises carbon (50-75 per cent reductions), saves costs (often 16-20 per cent or more), and enriches communities. While demolition suits irredeemable cases, defaulting to retention treats buildings as urban mines.

Policymakers must incentivise via bonuses and credits; developers adopt lifecycle metrics; engineers innovate disassembly.

Cities thriving tomorrow will layer new over old, creating vibrant, resilient palimpsests.

As our High Line walker knows, preserving the past builds a better future.

Next week, we are investigating the possibilities and drawbacks of car-free cities!

Ready to build a better tomorrow for our cities? I’d love to hear your thoughts, ideas, or even explore ways we can collaborate. Connect with me at info@fannimelles.com or find me on Twitter/X at @fannimelles – let’s make urban innovation a reality together!

Leave a comment