It’s 8 pm on a Tuesday in the summer. You’ve just stepped out of an air-conditioned office block in the CBD, expecting the cool relief of the evening air. Instead, you’re hit with a wall of heat. The pavement radiates warmth through the soles of your shoes, and the brick façade of the building next to you feels like it’s been baking in an oven all day—because it has.

This isn’t just a heatwave; it’s the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect. It’s the phenomenon where our cities—dense with concrete, asphalt, and glass—absorb solar energy during the day and re-emit it at night, keeping urban areas significantly hotter than the surrounding countryside.

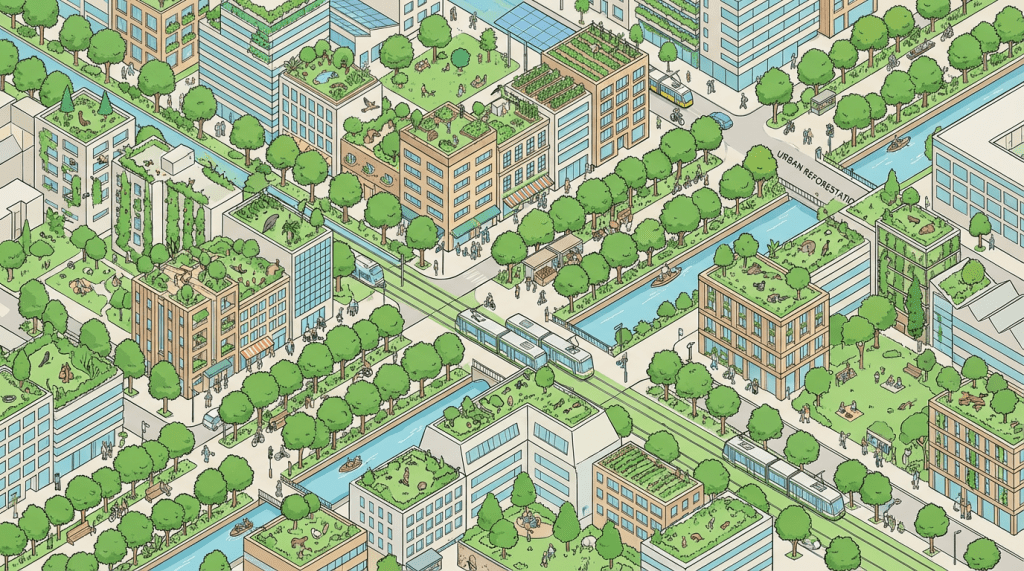

But as the mercury rises, so does the ingenuity of urban planners, engineers, and scientists. From the “green corridors” of South America to the high-tech skins of future skyscrapers, a revolution in thermal resilience is underway. Here is how the world’s leading cities are trying to turn down the thermostat.

What is the urban heat island effect?

The urban heat island effect happens when developed areas experience higher temperatures than surrounding rural zones. In cities, natural landscapes give way to impervious surfaces like concrete and asphalt, which absorb solar radiation and limit cooling through evaporation. Factors include low-reflectivity materials, urban canyons that reduce wind and trap heat, and human-generated warmth from vehicles and air conditioners. Temperature gaps can reach 15°F to 20°F, often more pronounced at night under calm conditions.

The consequences extend beyond unease, intersecting health, energy, and environmental realms. On health, urban heat strains the body, leading to heatstroke, cardiovascular issues, and respiratory problems, with vulnerable groups like the elderly at greater risk. It worsens during heatwaves, boosting mortality and non-fatal outcomes such as dehydration. Consider a family in a densely packed neighbourhood, sweltering without relief, facing heightened health threats amid rising temperatures. Energy-wise, heat islands spike cooling demands, raising electricity use by about 1.5% per degree increase and straining grids. This elevates costs and emissions from peak power plants. Environmentally, hotter air fosters smog formation and heats runoff, degrading water quality and aquatic life. These effects compound, creating feedback loops in urban settings.

It is also important to note, as Professor Sebastian Pfautsch highlighted in episode 392 on the What is The Future for Cities? podcast, that there are no urban heat islands, only the effect itself even though many resources only talk about the former:

Nature-based strategies in action

Cities are countering this with greenery that provides shade and evaporative cooling. The most intuitive way to cool a city is to stop treating it like a fortress of concrete and start treating it like an ecosystem. Nature has been doing air conditioning for billions of years through shading and evapotranspiration (the process where plants release water vapour).

In Medellín, Colombia, the Green Corridors initiative planted millions of trees and plants along roads and waterways, dropping temperatures by 2°C and cutting air pollution. This connected network not only cools but also reduces respiratory illnesses, blending environmental gains with community jobs. Picture locals strolling shaded paths, wildlife returning, transforming a once-stifling city into a vibrant haven.

Singapore, facing tropical humidity and space limits, integrates nature vertically. Kampung Admiralty achieves a green plot ratio over 100%, with terraced gardens harvesting rainwater and cooling public areas. Marina One’s “Green Heart” – a multi-level biodiversity space – enhances ventilation through aerodynamic design. The Digital Urban Climate Twin (DUCT) simulates heat scenarios for optimised planning. Residents enjoy breezy, green high-rises, a model for dense urban living.

In Melbourne, Australia, the Urban Forest Strategy targets 40% canopy cover by 2040, using diverse species for resilience. The Green Factor Tool mandates green infrastructure in developments, scoring elements like walls and roofs for heat mitigation. This ensures new builds contribute to cooler streets, fostering bird habitats and pleasant walks.

The built environment: Engineering the cool

Trees are fantastic, but they can’t be everywhere. In the dense cores of mega-cities, we need materials that work harder.

Los Angeles is famous for its car culture and the endless sprawl of black asphalt that comes with it. To combat the heat absorbed by these roads, the city launched a “Cool Pavement” pilot program, coating streets in neighbourhoods like Pacoima with a reflective grey seal. The physics works: these coated surfaces can be 10 to 16 degrees Fahrenheit (roughly 5–9°C) cooler than regular asphalt. However, the pilot revealed a tricky nuance in urban thermodynamics. While the ground was cooler, some pedestrians reported feeling hotter. This is because highly reflective surfaces can bounce sunlight upwards, hitting people from below—a metric known as Mean Radiant Temperature. It’s a valuable lesson: cooling the city requires a holistic view, ensuring we don’t just reflect heat from the road onto the pedestrian.

Tokyo is taking a lesson from history to solve a modern problem. The city is reviving the Edo-period concept of “Kaze-no-michi” or wind paths. By using supercomputers to model airflow, planners are redesigning the urban geometry to allow cooling sea breezes from Tokyo Bay to flush through the city centre. This involves making hard choices, such as demolishing “wall-like” buildings that block airflow and orienting new skyscrapers to channel wind rather than stop it. It’s about letting the city breathe.

Emerging solutions for the urban heat island effect

Planting trees? Coating surfaces? Directing wind paths? Emerging materials pushing boundaries? Scientists, innovators and city decision makers are now developing solution that can alleviate the effect:

- Passive daytime radiative cooling (PDRC) reflects sunlight and emits heat to space, achieving sub-ambient surfaces without power. This could revolutionise roofs and shelters.

- Retro-reflective materials direct light skyward, potentially lowering air temperatures by 5°F in dense cities. Thermochromic coatings adapt colours – dark for winter warmth, light for summer reflection – saving energy year-round.

- Digital Twins utilize artificial intelligence to create virtual replicas of cities, enabling planners to simulate and optimize microclimates, airflow, and shadow patterns for new developments before construction begins.

- Dynamic surface coatings change colour based on temperature—darker in winter to absorb heat and lighter in summer to reflect it—offering an adaptive solution for year-round thermal regulation.

- Vertical forests integrate high-density vegetation into high-rise architecture to filter pollutants, provide shade, and lower surrounding temperatures through evapotranspiration without occupying valuable ground-level space.

- Treated with titanium dioxide ($TiO_2$), smog-eating pavements chemically break down air pollutants upon UV exposure while reflecting solar radiation, simultaneously reducing the heat-trapping effect of urban smog.

- District Cooling Systems (DCS) replace individual building air conditioners with a central plant that pipes chilled water underground to cool entire districts, significantly reducing energy consumption and the expulsion of waste heat into city streets.

These innovations with blue-green infrastructure, permeable/porous pavements and proper shading promise adaptive, efficient urban skins to combat the urban heat island effect, when supported with proper information and research, as Professor Sebastian Pfautsch advocated for in episode 392 of the What is The Future for Cities? podcast:

There is no silver bullet for the urban heat crisis. A cool pavement might need a tree canopy overhead to protect pedestrians from glare. A high-tech PDRC roof in Melbourne needs to be balanced with winter heating needs. The resilient city of the future will be a hybrid. It will use the ecological intelligence of Medellin, the vertical density of Singapore, the policy rigour of Melbourne, and the material innovation of Tokyo. As summer bears down, the race to implement these solutions isn’t just about comfort—it’s about survival.

The tools and examples are already out there. The question is no longer whether cities can fight urban heat islands, but how quickly we act.

If you’re a city planner, developer, policymaker, resident or simply someone who cares about livable urban spaces, start small but start now:

- Plant a tree or support a local greening project in your neighbourhood

- Advocate for cool pavements, green roofs or better urban ventilation in your next council meeting

- Talk to your representatives about mandating green infrastructure in new developments

- Share this post and keep the conversation going

Every shaded street, every reflective surface, every breeze channel makes a difference. Cooler, healthier, more antifragile cities won’t build themselves – they need people like you to push for them.

What will your city look like in 2030?

Let’s make sure it’s a place people want to live in, not escape from.

Next week, we are investigating the role of government for urban futures!

Ready to build a better tomorrow for our cities? I’d love to hear your thoughts, ideas, or even explore ways we can collaborate. Connect with me at info@fannimelles.com or find me on Twitter/X at @fannimelles – let’s make urban innovation a reality together!

Leave a comment